Our memories: fact or fiction

‘Memory distortions’ alter recollections based on reference

Oct 7, 2014

Fiction and fact are often easy to differentiate.

But what happens when fact is confused with fiction and vice versa?

When it comes to memory, it’s not always reliable. In fact, it’s constantly being rewritten.

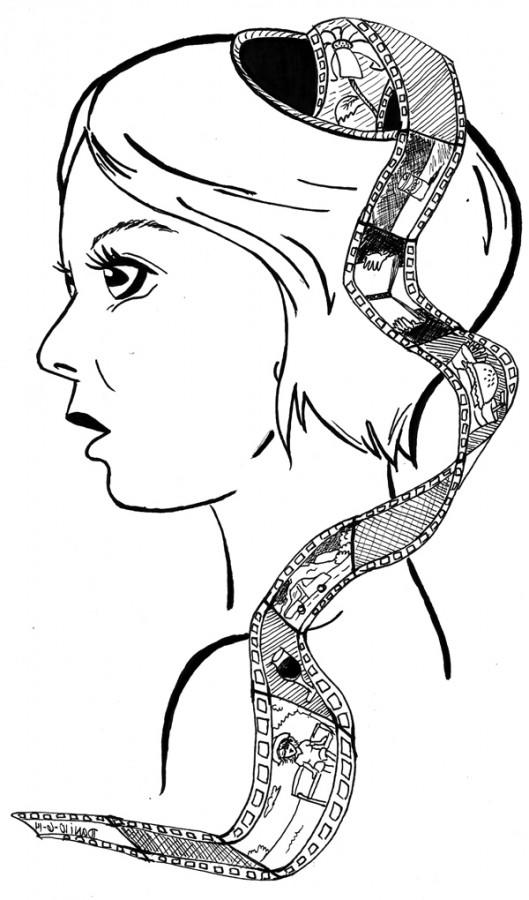

A memory isn’t an exact replica of what happened. It’s not like a video camera that captures the moment exactly as it happened. Instead, the captured footage is being edited, deleted, and rearranged each time the memory resurfaces.

“Memory distortions are basic and widespread in humans, and it may be unlikely that anyone is immune,” authors of a published study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) wrote.

Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and her colleague Jacqueline Pickrell have shown how easily memory can be manipulated in people.

In their study, Loftus and Pickrell tested the memories of their subjects by giving them three written accounts of events that had actually happened to them and one false memory of being lost in a mall between the ages of 4 and 6.

The false account was plausible — realistic details of the event were backed by the subject’s relatives and places the subject was familiar with.

Afterward, the subjects were asked to write down whether or not they remembered the event. If the subject did remember, he or she was asked additional details of the event.

The results revealed one third of the subjects reported the false event — either with partial or full recall. In their follow-up interviews, 25 percent still remembered the false event.

Subjects believed the false memory to be true, even going as far as describing the event with great detail and confidence.

Even people with remarkable memory are susceptible to having false memories.

In February 2011, several researchers at UC Irvine quizzed Frank Healy on his Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory to test him for accuracy and false memories as Erika Hayasaki, an assistant professor of literary journalism at UC Irvine recorded their conversation.

HSAM is the ability to remember specific events and details from the past, such as a dinner 10 years ago on a specific day. There are around 50 reported cases of HSAM in the United States.

Two years following the event, Hayasaki interviewed him on Nov. 18, 2013.

Hayasaki said, “When I interviewed Frank Healy this month about what he remembered about his visit two years and nine months earlier to UC Irvine, he got a lot right, but not everything.”

Healy recounted his memories of Feb. 9, 2011 — the day he was tested on his memory by UC Irvine researchers. He described the details of the day almost perfectly — from the long table, to the people sitting there. He also remembered writing down a series of numbers and letters on a green board with chalk.

But Healy did not write on a green board, or use chalk. In actuality, Healy wrote on a whiteboard and used colored markers.

In a PNAS study, Lawrence Patihis is the first to conduct a study on people. According to the study, the recollections of an individual with HSAM are correct 97 percent of the time.

Patihis noted the puzzling nature in how individuals with HSAM “remember some trivial details, such as what they had for lunch 10 years ago, but not others, such as words on a word list or photographs in a slideshow.”

He concluded that, “The answer to this may be that they may extract some personally relevant meaning from only some trivial details and weave them into the narrative for a given day.”

It is unnerving to know how easily memory can be tampered with. Memories often define us, but to what extent? The past, present and future are constantly being rewritten.