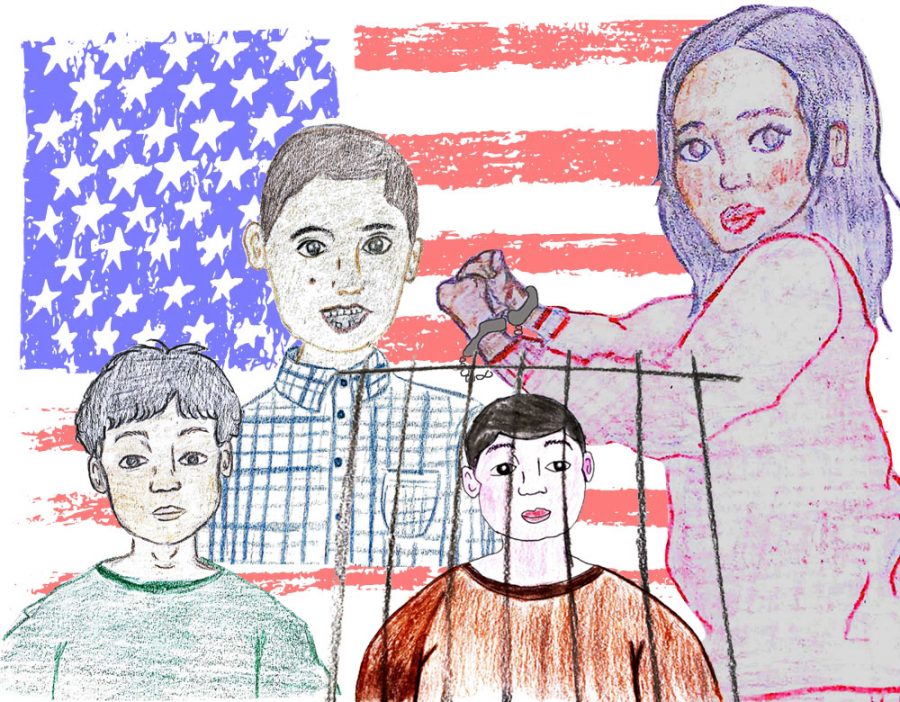

Migrant tales unite campus

the increasing price of liberty

Oct 2, 2019

Members of the Advocate Editorial Board show solidarity with Contra Costa College students from migrant families who feel their status or background will prohibit them from achieving their goals. Below, editors share personal migration stories from their home countries to the U.S. and the danger that shadowed their journeys.

Cindy Pantoja

I was born in the picturesque town of San Pedro Tlaquepaque, Jalisco in Mexico. My mom was a single mom and she was able to provide a modest life for us, but we didn’t lack anything.

As a 16-year-old, I was proud of the craftsmanship of my town. I dreamed of working in the tourism industry and spreading its history in as many languages as I could speak.

School in Mexico is expensive, but I had a well-paid job in the quality control department of an American swimsuit company. With the money I earned, I was able to afford to attend a private school that specializes in computer science and foreign languages.

Since I worked during the day, I could only attend school at night year around. One muggy evening in the summer of 2000, on my way to school, I was kidnapped by a stranger. He hit me in the back of my head and dragged me to his car. Even though I was in shock and paralyzed with fear, I fled the vehicle at a red light.

Two weeks later, my family and I suffered a murder attempt at our own house by an intoxicated person. My family was able to escape, but we knew that we couldn’t return to our home or our neighborhood because this person was going to try to end our lives again.

We had to put our fear aside and made the decision to save our lives. We decided to leave everything we worked hard for and attempt to enter the U.S. illegally and ask for asylum.

That same evening, we took a bus that would lead us out of harm’s way.

We arrived in Tijuana three days later.

Once there, we were separated and crossed the border in different cars. My mom and my 9-year-old brother crossed successfully, but I got caught by an immigration officer.

I was separated from the adults I was traveling with, since I was a minor.

I was detained in a waiting area with other kids. Night came, and we were not offered food, water or blankets. We had to sleep on the cold plastic chairs in the waiting room.

I successfully crossed the border a few weeks later. I travel by train to San Diego, then by airplane to Oakland, where I graduated from high school two years later.

After high school, I went to Laney College, where I majored in graphic arts, but didn’t graduate because I didn’t have enough money to continue with my courses.

I’m 35 years old now, I haven’t been able to fix my status because of the deportation that I wasn’t even old enough to comprehend — these people made me sign a bunch of papers in a language I didn’t understand.

The road to legalizing my status hasn’t been easy, but it hasn’t stopped me from living a meaningful life. I got married, formed a beautiful family. I’m a published writer and now I’m back in college pursuing a degree in journalism.

In the future, I would like to have my own publication where I can give a voice to all the stories of the hard-working people who live in my community.

Luis Cortes

I was brought to the United States of America from Mexico when I was 6 years old. I was born in Mexico, along with my mother and two sisters. My father brought us here in 2001 in hopes of a better life and greater opportunities.

I had no idea what was going on. All I remember was leaving my house in Michoacan, Mexico. The following day I was in a new place surrounded by my family, my mother, my father and my two sisters.

I was confused about where I was, but my father introduced my siblings and I to my aunt and uncle and their children.

This new place was Moreno Valley, California, however, I have lived in the Bay Area for the past 17 years.

Growing up as an undocumented immigrant I did not foresee the challenges I would face as compared to those born in this country. As a child, I believed that my classmates and I had the same chances and rights to accomplish our goals. If they wanted to become an astronaut they could, and so I believed I could as well.

I came to realize that was incorrect.

I learned that I could not get a job, apply for a loan, join the military or get a driver’s license because I wasn’t born in the United States.

Because of this, I was forced to work harder than my contemporaries.

My passion for sports and writing ability drove me to journalism. The work ethic instilled in me by the inability to share the same privileges as those born in a country that preaches equality, will one day make me the success I merit.

Denis Perez

I have always downplayed what being undocumented means to my life. It means living unapologetic and persistent to the truth that this land is as much mine as it is yours, despite false white supremacist erected borders.

I was brought into this country as a 4-year-old and was given access to a land of opportunities in 2001.

My mother gave my siblings and I to a coyote and trusted that I would be safely transported from Tijuana into San Diego. I was to pretend I was asleep and false documents would prove that I could enter the U.S.

My brother and sister did the same in other vehicles.

Meanwhile, my Guatemalan mother and father crossed a desert together alongside other migrants. There was no assurance I would see them, or that they would reunite with me and my siblings.

Yet, we persisted.

My parents left an unstable economy in Malacatan, San Marcos, Guatemala and settled in Chiapas, Mexico. But violent conditions and disappearing job opportunities did not allow them to settle permanently.

So, with three children and a dream they came to the Bay Area.

Now here, I am a journalist. I have reached the highest levels of collegiate journalism and am a local reporter more than worthy of the title photojournalist.

In Mexico, journalism is under attack and death is a common path in the profession.

In the Bay Area I was given an opportunity to develop a dream and pursue it. Sure, that can happen anywhere. But for me, it was best that it happened here, in my home — the East Bay — where I live undocumented, unafraid and free.

Jose Rivera

My journey to America started with many problems that as a kid I never knew about, the only thing I remember is that I was in my room watching TV, my mom approached me and asked me if I wanted to travel with her to a different country.

I always wondered what was going on, but the only thing I knew was my mother never had the same support any of my uncles or aunts (who were university graduates) had from our family.

On March 2014, my mom and I were dropped off and since then our journey began.

I have always been afraid of sharing my whole story because of what people would think — I was afraid of how they would look at me.

However, now I can say that I, as a 12-year-old spent 4 days in an immigration prison cage with no showers, or drinkable water and with the same clothes for the entire time.

The floor wasn’t soft either, it was solid concrete. Each room was filled with more than 50 people ranging from 9-year-olds to 40-year-olds.

The smell of the place wasn’t good either.

Imagine the smell that one of these rooms with 30 people and no showers would be like.

Most of these people had spent more than 10 days inside. They were people that I met and spoke to and clearly remember.

I was one of the few lucky people that only suffered 4 days in confinement and till this moment, 6 years later — I still remember every single detail like it was yesterday.

March 21, 2014 was my first day at Mira Vista Middle School in El Cerrito. It was the beginning of a lot of new experiences, things that I never imagined existed.

My high school journey began in fall 2015 and I graduated in 2019.

Now, I’m in college majoring in journalism because I feel like this is one way for me to help people of all backgrounds, races and colors to share their stories and let other people know that we exist.