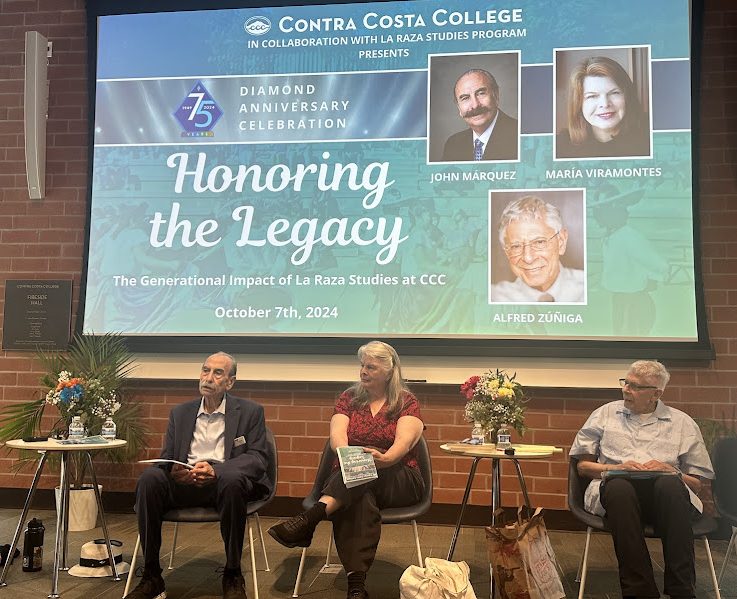

Contra Costa College held a panel with the founders of its La Raza program on Monday, Oct. 7.

The panel consisted of current Contra Costa Community College District trustee and former student John Marquez, former student Maria Viramontes and former head of La Raza Studies, Alfred Zuniga, who is now retired. They were part of the founding of La Raza in the 1970s, an integral part of Latin American culture at Contra Costa College.

The panel began with Contra Costa College President Kimberly Rogers giving thanks and announcing the guest speakers. The panel was handed over to former student and president of the La Raza Student Union Ricardo Sanchez and current La Raza Student Union Vice President Juliana Espinosa to ask the questions of the panelist.

The beginning of the panel started with a moment of silence for the victims in Palestine and Israel at Zuniga’s request.

“In one year, over 41,000 people have been killed,” Zuniga said. “To put that in perspective, the Vietnam War lasted over 10 years; the United States lost 56,000 over 10 years.”

Sanchez started the panel by asking Marquez and Viramontes about their experiences as students and why they wanted to emphasize Chicano culture. Marquez and Viramontes were founders of La Raza.

Marquez shared how he was a paratrooper and took care of his family while going to school. As a student, Marquez stayed involved with the community, joining the United Consult of the Spanish Speaking organization. As a student, he remembers going to meetings and wondering what they should call themselves. For hours, they would argue if they were just Mexicans, Spanish speaking or Spanish surnames.

After getting together, the group started calling themselves the Latin American club as Marquez said “we don’t know what else to call ourselves.” After finalizing a name, the members went to the library and took a count of Latino students –a total of 213. Marquez described that number as a relative “handful.” With CCC being predominantly African American at the time, the club didn’t see that much representation.

After considering the low count of Latino students, Marquez and other students went to high schools to promote that college was free and that there would be an established Latino culture at CCC. Marquez said he met Viramontes while she was a senior in high school and encouraged her to join the college.

Viramontes highlighted the tensions of the time such as the Vietnam War, political assassinations and riots. Her main concern was her safety during her college experience, she said, and with the help of the club, she was able to apply and be accepted to University of California, Berkeley. Her first day at Berkeley there was a riot, and she decided to turn around and go to CCC, where she felt safe.

“We still need to go out into the community and get the students that aren’t coming here,” Viramontes said at the panel. “We still need to help them fill out their applications and give them the encouragement they need… and when they get scared we need to stand by them”

“You have a little extra responsibility with that to encourage them to be free of their cultural norms of women,” she continued.

Continuing as a student, Viramontes wanted to make more than just a community at CCC, wanting to see Latino history, literature and arts. Viramontes took part in strengthening the middle college and establishing mentorships, as she saw that’s what students needed.

They went on to say how the main struggle they went through to found La Raza was that Latino culture was not an area of academic study yet. They come down to the decision of making their own department and making it its own style of interdisciplinary work, as well as getting recognized as a group of need.

Zuniga said he resigned from his position because of the way he was being treated, so the club took over. With Zuniga out of the picture, the club took action by protesting in front of then-CCC president Robert Wynne’s office. The plan was to be there until they had to be dragged to jail, prepared with toiletries and extra sets of clothes.

With the president essentially trapped in his office all day, he gave in and told his assistant to “give them whatever they want” and went home, allowing Zuniga to return and providing funding to La Raza studies. Zuniga shared a letter that the Latin American Student Union, as it was then called, sent to then-president Wynne when he first started, stating that the club did not have anyone else running the program and if they were to pick anyone else, that person would not be sufficient enough for the program.

Zuniga went on to share how he was not prepared to start such a movement. “I was just looking for a job,” but it grew into so much more, he said, adding that Marquez, Viramontes and others made his job so easy with the ideas and the fight for establishing La Raza.