Film clears fog of ignorance

Historical facts expose system of oppression

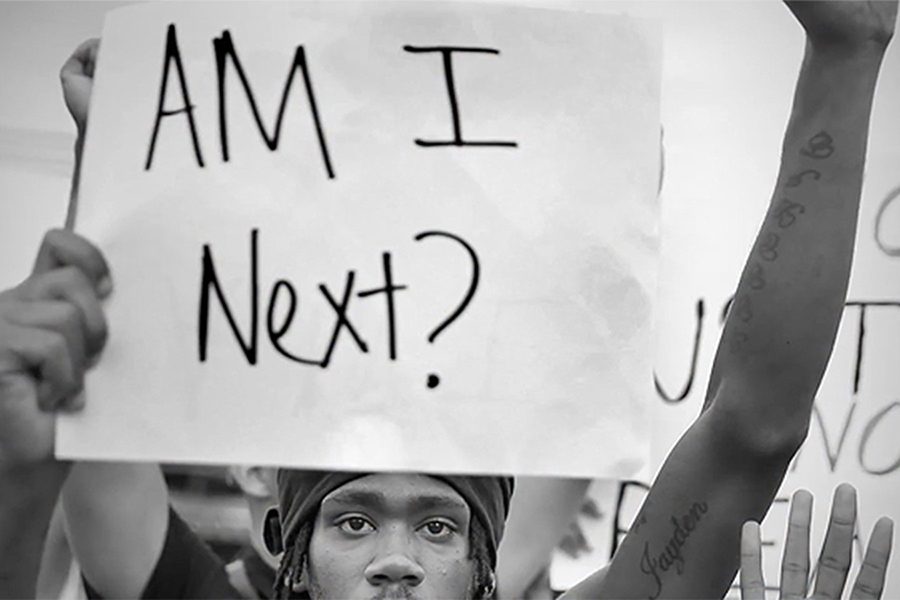

In a photograph from the film “13th,” a protester holds up a sign stating, “Am I Next?” referring to the possibility of his death at the hands of police. “13th,” directed by Ava DuVernay, explores the historical oppression of black communities and the mass incarceration of African-Americans starting from the end of slavery in 1863 to the present day police brutality epidemic.

Oct 21, 2016

Director Ava DuVernay plunges viewers into the historical oppression of African-American communities by the American justice system in her documentary “13th,” currently streaming on Netflix.

The film gets its name after the 13th Amendment of the United States Constitution that granted freedom to all Americans, including slaves. It highlights the clause that takes away that same freedom once a free citizen has been convicted of a crime.

The documentary, comprised of interviews with scholars, politicians and activists intertwined with footage of riots, police shootings and speeches, engages audiences of all walks of life to stop and think about American political views through the perspective of African-American communities.

The film pours so much rich information into the one hour and 40 minute run time that viewers might just want to sit, watch attentively and even take notes to get the full experience. Early in the film, DuVernay explores the aftermath of the Civil War in the Southern states.

Left with its economy destroyed, the South rebuilt its economy by exploiting the 13th Amendment’s backdoor clause allowing free people to return to slavery after the commission of a crime.

The South imprisoned masses of African-Americans on petty charges labeled the (Black Laws) to maintain a labor force without requiring compensation. This notion of second-class citizenship bled into popular culture, bolstered by popular films like “Birth of a Nation” which fortified the perspective that racist white Americans had of black people.

The film continues, covering the rise of the Ku Klux Klan’s influence in American culture. It defines this new era of terrorism toward black people that came in the form of lynchings, mob killings and extreme racism.

The conditions forced blacks to find refuge throughout the U.S. in what is known as the great migration from the South. DuVernay’s film transitions smoothly from era-to-era, exploring in it the last era’s influence and the re-occurring theme of black criminalization under the guise of maintaining public safety.

For example, during President Richard Nixon’s term in office (1969-73), the same influences of the Ku Klux Klan that branded African-Americans as criminals made it possible for Jim Crow laws and segregation to be acceptable despite lynching death statistics decreasing.

Furthermore, a perceived white moral high ground allowed Nixon to get away with racism in his policies by lying to the public. This strategy made it possible to arrest leaders of the Black Panthers and black power movements.

The approach was successful enough to shut down anti-war and gay liberation movements. One part when anger strikes viewers in the film is when Nixon’s adviser John Ehrlichman is heard explaining Nixon’s strategy for getting rid of protesters of the time.

Ehrlichman said, “…by getting the public to associate marijuana with hippies and blacks with heroin and criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

Deeper into the film, it explores the administration of President Bill Clinton. From 1990 to 2000 under Clinton, the prison population in America rose from 1.2 to 2.5 million. The prison system at the time of Clinton was heavily lobbied for and legislation was introduced to benefit the profits of corporations rather than the country. This happened mostly at the expense of black lives.

The film shows, throughout the history in America and continuing until today, that African-American lives are seen as disposable. One of the greatest parts of “13th” is the relevance it holds when tying history to modern day police brutality.

When most people are trying to move on from America’s sins, this film states that the true problem is the lack of serious dialogue on the subject.

DuVernay doesn’t clearly state a solution to this problem, but gives a warning to her viewers that racism will always reinvent itself. And although America is moving into an era where mass incarceration rates must go down, the conversation must be as realistic as the scores of African-Americans who face death at the hands of racism.

At the end of this film the viewer is left thinking about what the meaning of #blacklivesmatter is. And until black lives truly matter, no Americans will be able to truly experience living as free people.