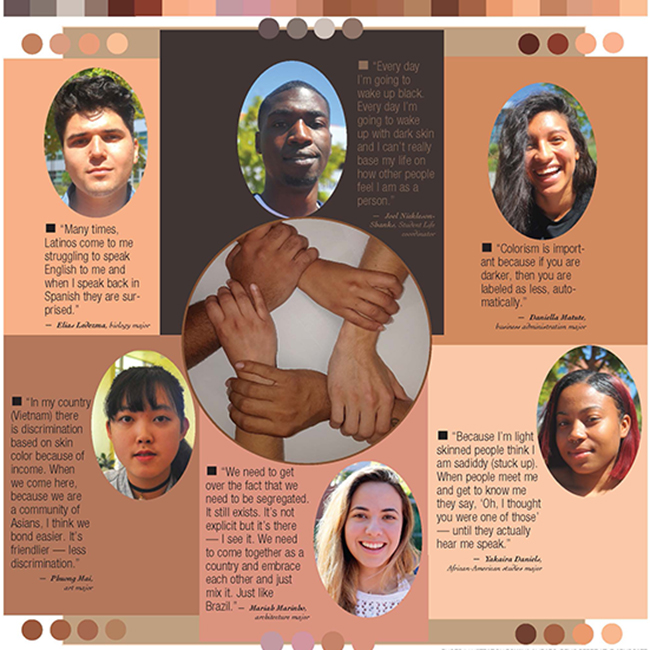

Snippets of shade

Sep 28, 2017

Dark things can be mysterious, intriguing, stunning or sleek. But when it comes to skin tone, across gender or geographical borders the sentiment more often than not is darker is less desirable.

Colorism, a term coined by author and activist Alice Walker in 1982, is a type of discrimination that highlights the way people are treated according to skin tone.

Despite the stark contrast between white and African-American skin in the U.S., the condition far outreaches American shores and permeates the boundaries of nearly every country in the world.

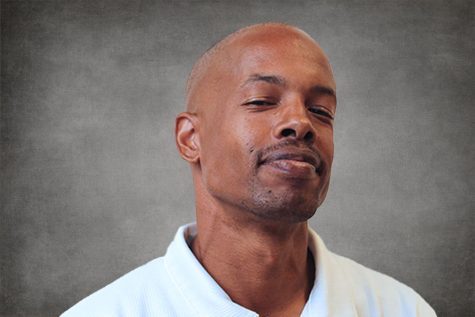

“It’s not just America,” Student Life Coordinator Joel Nickelson-Shanks said. “I travel a lot and in pretty much every country that I’ve been to people with darker skin get discriminated against. In America, I feel like it’s more of a way to pit black people against each other.

“People always go back to the slave example of light people being in the house and black people being in the field, I think it’s way bigger than that. We tie a lot of beauty to being light skinned — sometimes it’s seen as being closer to white.”

This sentiment is easiest explained through the paper bag test.

Throughout white and many African- American organizations in the early 20th century, a brown paper bag was used to determine whether or not someone would receive privileges that only people with a skin tone lighter than a brown paper bag were afforded.

Since this country’s inception, whiteness has been a symbol of purity and beauty, but in countries that are devoid of Caucasians, what feeds the discriminatory beast that is colorism?

Computer science major Jagjot Saggar is from India and says the divisions there are mostly driven by geography and a lack of education and opportunity.

In India, lighter skinned people live in the northern part of the country, while darker people occupy the poorer south.

“Sometimes it can be dangerous for northerners to go to the south because of potential muggings,” he said. “But if the people are educated there is generally no problem. The areas are far apart. Here we don’t have the same divisions, mostly because of education. There are a lot of Indians in the medical field and the tech industry. Dark and light, the opportunity for advancement in the U.S. is the unifying bond.”

For some, the brown-bodied pursuit of a better life or higher education can be challenging to navigate, especially in a world of covert or passive discrimination.

“I take classes at Diablo Valley College (in Pleasant Hill) as well as here and I’m basically the only Latina in class,” business administration major Daniella Matute said. “When I walk the halls I can feel people just staring. I don’t know if it’s because of my color or because I’m a girl or because I’m tall.

“I come from Nicaragua and there are a lot of dark people there. When I was a kid I didn’t know color. It wasn’t until I got here that it was an issue. Color is important here because if you are darker, then you are labeled as less than, automatically.”

With lighter Hispanics, acceptance can be fleeting because, in most cases, racial commonalities outweigh unification by pigmentation.

“It’s kind of a positive and a negative because with other people they see me as more trustworthy because I’m lighter and they talk to me more openly,” biology major Elias Ledezma said. “But when it comes to my fellow Latinos, they automatically assume that I can’t speak Spanish or that I know nothing about my culture.

“Many times, Latinos come to me struggling to speak English to me and when I speak back in Spanish they are surprised.”

Ledezma said his family comes from Jalisco, Mexico where people have lighter skin. “I’m still pretty distinguishable because my facial features are Latino.

“My dad told me that back home people with lighter skin were a little more arrogant. But here it doesn’t matter as much. It’s all about race. In Mexico, we are all Mexicans so it can’t be about race, only skin tone.”

For others, the path to acceptance can be tougher to navigate.

Sam Hernandez, who is studying to be an X-ray technician, said, “People see me and it’s like, oh no, because I’m brown.”

Hernandez said he gets mistaken for other races like Filipino or Indian, but when people learn that he is Mexican, because he’s brown, they assume that he only speaks Spanish and treat him differently.

In America, the lens in which people judge color can be the difference between opportunity and misfortune — even life and death.

“The whole light skin, dark skin thing offends me and it divides us as black people,” African-American studies major Yakaira Daniels said. “We are already separated from the world, so why separate us from ourselves. Why not stick together because everyone else is against us. Because I’m light skinned people think I’m sadiddy (stuck up). When people meet me and they get to know me they say, ‘Oh, I thought you were one of those’ — until they actually hear me speak.”

Nickelson-Shanks said colorism within racial groups is akin to being ashamed of who you are and a product of not knowing about your culture and history.

“I can’t be mad at people for being ignorant,” he said.

Brown Americans, black people in particular, shoulder the unfair burden of acquiescing to the insecurities of others to avoid unnecessary confrontations.

“Being tall, dark and male I find myself smiling a lot more to make other people feel comfortable. If I don’t, sometimes my regular resting face may make people feel uncomfortable. So I watch my mannerisms and my wording — a lot. You get used to it just like anything in life. It’s sad that it’s something that has to be accepted. But there are bigger issues that I want to address first.

“Every day I’m going to wake up black. Every day I’m going to wake up with dark skin and I can’t really base my life on how other people feel I am as a person,” Nickelson-Shanks said.

Wealth and education inequities drive these divisions. However, some immigrant communities leave those divisions behind upon reaching the shores of the U.S.

“I don’t pay much attention to skin color. I don’t think there are any real differences,” art major Phuong Mai said.

“In my country (Vietnam) there is discrimination based on skin color because people are darker, or because of income. When we come here, because we are a community of Asians, I think we bond easier. It’s friendlier —less discrimination.”

For some, like architecture major Mariah Marinho, the widespread self-segregation that happens in America is at the root of colorism and racial discrimination.

“People either say I’m white or Hispanic, but I’m not. I’m Brazilian,” she said.

“Over there we’re mixed. We don’t have whites from Portugal or blacks from Africa. We’re all mixed, so we don’t see it the same there.

“We need to get over the fact that we need to be segregated. It still exists. It’s not explicit but it’s there — I see it. We need to come together as a country and embrace each other and just mix it —just like Brazil.”