Genocide of natives shifts opinion on cultural holiday

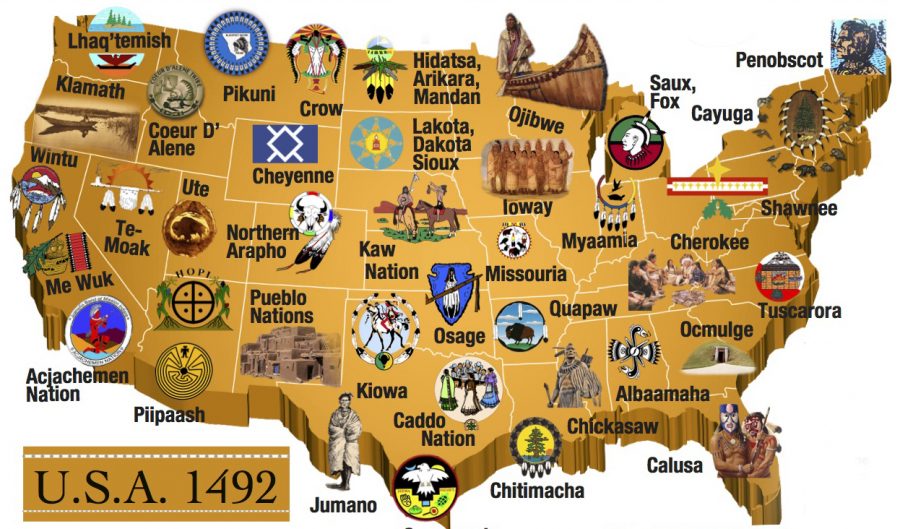

A partial map of native tribes and nations in the United States before the Columbus colonization period.

Nov 1, 2017

Cities throughout the nation continue to adopt Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus Day as that holiday holds a dark past of the torture and murder of millions of Native Americans.

Christopher Columbus sailed the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 and colonized Native American land.

“Why celebrate a terrorist instead of celebrating the Native Americans and talking about what really happened in the U.S.,” Contra Costa College psychology major Enrique Duarte said.

Duarte said it’s important to learn the truth and not the lies about what happened to Native Americans on their land 500 years ago.

The Geneva Conference held on Sept. 23, 1977 in Geneva, Switzerland, established Oct. 12 as the international day of solidarity with indigenous people of the Americas.

With this decision, native people took a stride as it was their first time to speak for themselves at a United Nations conference.

At the conclusion of the conference, Columbus Day was deemed International Solidarity Day with American Indians.

“It means that we have made a very large part of the world recognize who we are and even to stand with us in solidarity in our long fight. From now on, children all over the world will learn the true story of American Indians on Columbus Day instead of a pack of lies about three European ships,” John Curl, founding member of the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Committee wrote on Berkeley’s Indigenous Peoples’ Day website (ipdpowwow.com).

In the 1977 Geneva Conference supporting native recognition, over 60 indigenous peoples and native nations were represented, including Argentina, Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru.

The resolution in the 1977 Geneva Protocol states that evidence brought forth by the native people was enough to prove the discrimination and genocide committed against those communities.

“Brutal colonization paved the way for the plunder of their land and resources by commercial interests seeking maximum profit. The massacre of millions of native peoples for centuries and the continuous grabbing of their land deprived them of the possibility of developing their own resources and means of livelihood. The denial of the self-determination of indigenous nations and peoples destroyed their traditional value system and their social and cultural fabric.”

These acts resulted in the destruction of the indigenous nations.

Although some people lean toward changing the name of the holiday from Columbus Day to Indigenous Peoples’ Day to commemorate and honor those cultures, some less invested activists see it as just another day of the week.

Many show their support for changing the holiday’s name by putting on festivals or other community gatherings.

In October of 1992, Berkeley was the first city to get rid of Columbus Day and begin the Oct. 12 Indigenous Peoples’ Day holiday.

Berkeley celebrates the day by annually hosting an Indian market and Pow Wow.

This year it was canceled due to the unhealthy air quality lingering through the city caused by Napa and Sonoma wildfires, Indigenous Peoples’ Day Coordinator Gino Barichello, on behalf of the Indigenous Peoples’ Day Planning Committee, wrote on Berkeley’s Indigenous Peoples’ Day website.

The event holds space for Native American dance, songs, foods and arts and crafts.

Just this year the state of Ohio and the city of Bangor, Maine abolished Columbus Day and embraced Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a holiday.

CCC biology major Luis Gonzalez said knowing the history of the U.S., the genocide and the fact that Native Americans were robbed of their land, there isn’t a “real” reason to celebrate Columbus Day.

“I think it’s more important that we celebrate indigenous people and, most importantly, celebrate their resistance because they are still here.

michel • May 30, 2020 at 10:38 am

I find this to be offensive. Cherry picking information to justify or minimize how white colonizers raped, killed, tortured, subjugated, enslaved, destroyed communities, and ultimately wiped out whole Native American nations is vile. This thought process is part of white supremacy and the systematic racism that still exist today. Violence is never the answer but violence with out provocation is sadistic and violence in response to violence, although not the answer, is understandable.

Shasta • Dec 16, 2019 at 9:35 am

I completely agree with Grace on this matter. History has been white washed by the people who writre the history books. In any case, if a foreigner came to my land and killed and supplanted my people, I would do the same as the Indians did at the time.

Your version of the truth is a false one- go seek the truth.

Read ‘American holocaust’ by David Stannard

Grace • Nov 5, 2019 at 9:06 pm

@Baracutey Are you aware these accounts were written by white people and may obviously have been forged in their favor? If I were Native American at the time, I would have most certainly taken such these actions too.

Baracutey • Nov 1, 2017 at 11:18 pm

““Why celebrate a terrorist instead of celebrating the Native Americans and talking about what really happened in the U.S.,” Contra Costa College psychology major Enrique Duarte said.”

Why celebrate Native Americans over that “terrorist” you condemn when historical fact shows that they also behaved in the same manner:

Account of Rachel Plummer, June 1836 (Texas)

“In her account of her life among the [Comanche], Rachel wrote that six weeks after giving birth to a healthy son, the warriors decided she was slowed too much by childcare, and threw her son down on the ground. When he stopped moving, they left her to bury him. When she revived him, they returned and tied the infant to a rope, and dragged him through cactuses until the frail, tiny body was literally torn to pieces.”

—————————-

Account given to me by descendant of William Overall, 1793 (Kentucky)

Chief Doublehead [Cherokee]- His most infamous atrocity occurred in 1793 when he murdered Captain William Overall and a companion in Kentucky, stripped the flesh from their bones, roasted it, and ate it. He carried their scalps to Indian towns that were at peace with the whites and aroused the young braves to join his war party.

—————————-

Ranch incident, November 25, 1839 (Florida)

Shortly after the mail wagon left the city Dr. Philip Weedman, Sr., accompanied by his little son, a lad about twelve years of age, both in an open wagon, with Mr. Graves, on horseback, left for the purpose of visiting his former residence… On arriving at the commencement of Long Swamp, without any previous warning, he was fired upon [by a Seminole band] and killed, having received two balls in his breast; his little son was wounded in the head, baring his brain; also cut with a knife. The mutilated youth, with the remains of his dead father, were brought in town today.

—————————-

Theater Troop Attacked May 27, 1840 (Florida)

“We learn from a passenger in steamer General Clinch, Capt. Brooks from Black Creek, that on Saturday forenoon, between 9 and 10 o’clock, Mr. Forbe’s theatrical company, with some others, were on their way from Picolata to St. Augustine, and within five or six miles of the latter place, (the party occupying two wagons,) when the wagon in the rear was attacked by a by Coacoochee [Miccosukee] and his band. Mr. C. Vase [was] killed and mutilated. Two others are dead… part of Mr. Forbe’s company.”

—————————-

Unburying the hatchet of war only gets your hands stenched with the same hatred it was buried with it a long time ago… Learn from history that humans are still guilty of inhuman behaviour and work to rectify this starting with your own selves.