Talks offer false solutions

23rd Conference of Parties evades discussion of reparations for environmental damage

Dec 11, 2017

Industrialized nations are holding back climate leadership by women, indigenous peoples and developing nations because they are unwilling to pay reparations for the social and environmental damage caused by industrial greed.

The COP23 or the 23rd Conference of Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that took place last month in Bonn, Germany reveals this continuing trend that has been the main obstacle impeding taking effective action on the climate crisis.

The conference is led by the island nation of Fiji, but it took place in Bonn because Fiji was unable to accommodate such a large conference.

The inability to accommodate the gathering was due to its storm season which has been exacerbated by climate change.

Fiji’s goals were to address the roles of women in climate leadership, secure the rights indigenous peoples and to bring the health of the world’s oceans to the forefront as a climate issue.

The result of Fiji’s work to bring a balance of gender to the climate negotiations process was the development of the Gender Action Plan (GAP).

The GAP outlined a lengthy methodology to improve the participation of women in leadership roles in the UNFCCC.

However, the question may be which women the UNFCCC is willing to listen to.

Taking place in Bonn, along with the climate conference, was “Women Leading Solutions on the Front Lines of Climate Change.”

This event was held by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN).

WECAN grew out of the Women’s Earth and Climate Caucus which began in 2011.

The organization has held a number of events alongside UN climate conferences as well as its own events focusing on bioregional and indigenous knowledge, and has taken action against the Keystone XL pipeline.

The group promotes principles such as rights of women and indigenous peoples and the rights of nature and future generations.

The voices of the panel of women leaders radically conflicted with many of the core principles that the industrialized nations promote as sustainable solutions at COP23.

Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs that were set forth two years ago as part of the Paris Agreement are the commitments of individual nations to decrease carbon emissions.

Many of these commitments rely on “financial instruments” such as carbon trading to bring about carbon reductions.

The problem with carbon trading is that the system allows industries to continue to pollute in exchange for purchasing carbon offsets, which represent projects intended to reduce carbon elsewhere.

This creates pollution hot spots, such as our home in the North Bay, where refineries would be able to continue to pollute at levels that are dangerous to public health — as long as they purchase the offsets.

The details of what is allowed to function as a carbon offset has drawn criticism from indigenous communities.

Portions of forest have been set aside, in effect privatized and tribes have been disallowed from maintaining their traditional foodways on the reserved lands.

Destructive forest practices such as clear-cutting in Northern California also represent carbon offsets.

Another controversy that involves the “financial instruments” that industrialized countries stubbornly cling to is the issue of “loss and damage.”

Loss and damage has a long history that goes back to the early days of climate negotiations. Industrialized countries have avoided this discussion for decades because it leads to the central question of liability.

That is, who pays for the loss of life or land base and the damage to property that is the result of anthropogenic (human caused) climate change?

Event attribution is a field of research in which scientists determine the degree that an extreme weather event is related to climate change.

Even the mention of this field is considered political.

Developing countries and the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) have long been pushing for loss and damage to be considered a major issue in the negotiations.

Finally, it has been recognized as a “major pillar” of the negotiations in Bonn.

Loss and damage, as well as pre- and post-2020 funding from industrialized nations for the non-carbon intensive development and poverty relief of the developing nations, has led to what is known as “bifurcation” at the climate negotiations.

This is the divide between developing nations that need funding and support to address climate change — and the wealthy industrialized nations who caused it.

Industrialized nations skirted their own liability by forcing a compromise.

Nations that are most susceptible to the destructive effects of climate change would be able to purchase “low-cost” insurance as opposed adhering to the familiar adage — you break it you buy it.

The compromise was reached by including desperately needed funds from the Kyoto protocols into the pre-2020 funds.

Commitments to the pre-2020 funds, made by industrialized nations during the Paris Agreements, have fallen short of their mark.

Once 2020 rolls around, industrialized nations are slated to contribute $100 billion a year to developing nations as part of the Paris Agreement.

With the U.S., the world’s second largest polluter, promised to pull out of the agreement in 2020, it is unclear how the $100 billion a year commitment will be met.

Up to $100 billion a year sounds like a formidable commitment, but many have questioned whether that amount is sufficient. A number to compare this to might be the U.S. military budget which was up to $598 billion in 2015 and 2016.

In 2017, it dropped down to just over $520 billion.

The $100 billion goes into a global fund for developing and underdeveloped nations. This is in intended to support economic development and reduce poverty on a de-carbonized pathway.

That is, a pathway that does not add massive amounts of carbon to the atmosphere as industrialized nations have.

Developing nations are expected to produce carbon in their development process, but the $100 billion a year global fund may allow for those countries to build sustainable infrastructure.

Also, in 2020, industrialized nations are slated to put their NDC’s into effect. The NDC’s were one of the most contentious and difficult points of the negotiation process in Bonn.

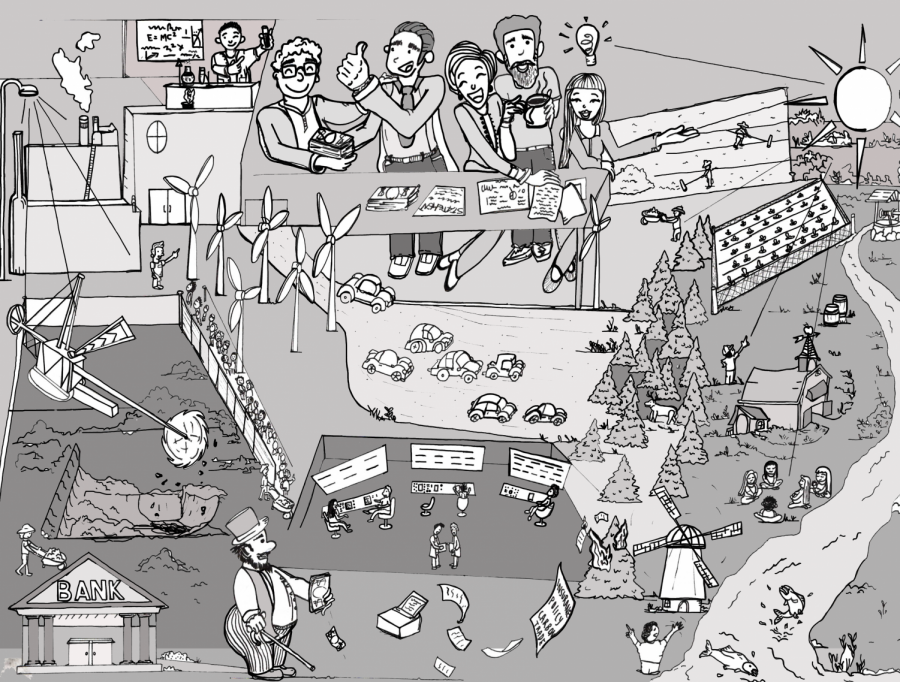

The reason that industrialized nations are so attached to what they call “financial instruments” is that industry leaders, who have a very powerful role in the climate negotiations, want to continue to earn profits. They hope to maintain a constant revenue stream throughout the process of transitioning to a carbon neutral infrastructure.

The idea that industrialized nations are liable for the damages caused by the effects of climate change has been criticized. Some people believe it is similar to African- Americans demanding reparations for slavery.

The late Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano chronicled the connections between slavery and industrialization in his classic “The Open Veins of Latin America.”

Galeano’s point is that slavery was used to extract the gold and the silver as well as other resources that were then used as the economic fuel to power the industrial revolution European nations.

Now Western industrialized nations want the world to forget about both their historical carbon emissions, as well as their use of slavery in the process of that industrialization.

Slavery and the theft of resources, created a global economy controlled by white western nations. The resource theft and enslavement continues today, shrouded behind loans and interest payments due from the very people whose resources and labor were stolen to create the wealth that those loans originate from.

Western nations have used their “financial instruments” and military might to keep the colonized nations of the global south underdeveloped and dependent.

Western nations and their industry leaders that now control a white supremacist global economy did not earn their wealth — they stole it.

It is no wonder the UNFCCC has to create complex lengthy strategies to bring women into leadership roles because women are among the most subjugated.

The global climate challenge that we are facing is taking us beyond concepts of profit.

As we approach eight billion people on a planet with a destabilizing climate, wealthy industrial leaders will need to forgo their profiteering from the labor and resources of women, indigenous peoples and the nations south of the equator.

Ryan Geller is a staffer for The Advocate. Contact him at [email protected].