Professors with adjunct status suffer exploitation

Full-time employment figure attracts district scrutiny

Mar 20, 2018

Adjunct professors have become a reliable underclass who are exploited as a quick fix for budget woes despite longstanding statewide and national recommendations calling for more full-time positions to support student success.

Many part-time professors are forced to piece together full-time work from different districts to afford the high cost of living in the Bay Area, earning them the dubious nickname, “freeway fliers.”

The maximum load allowed by the state for faculty to be considered part-time is 67 percent, the equivalent to about two or three classes. Without a variance, teachers who exceed 67 percent would become entitled to the benefits and pay of full-time employees. This has created an incentive for colleges and universities across the state to employ more part-time workers who can be paid less. This trend was recognized as a problem more than 30 years ago.

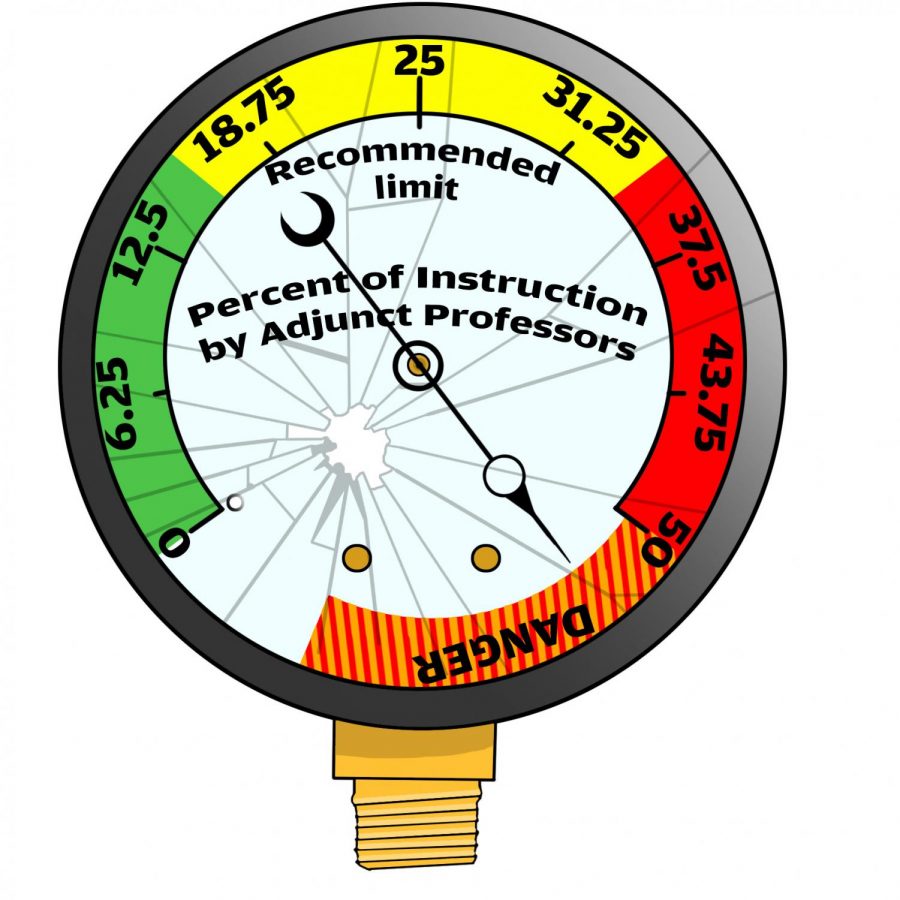

In 1988, Assembly Bill 1725 outlined recommendations that 75 percent of student instruction hours to be provided by full-time professors, according to Eugene Huff, executive vice chancellor of administrative services at the Contra Costa Community College District.

The district has reported full-time faculty percentages ranging from 48.56 percent to 54.65 percent over the past 10 years, according to United Faculty Executive Director Jeffrey Michels.

“The ratio as measured by the weekly student contact hour matrix is currently at 56.4 percent full-time in the district. That means that 56.4 percent of credit instruction (not instructors) is taught by full-time employees,” Executive Director of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges Jonathan Lightman said.

“There is a clear relationship between the rate of full-time faculty instruction hours and student success,” Michels said. “When we rely on part-time faculty, when we don’t pay them a living wage or give them job security and adequate health care, the quality of education suffers.”

Adjunct professors expressed difficulty in finding time to meet with students because they are only on campus during specific hours.

Adjunct English professor Brandon Marshall said, “We are only paid for class time and a minimum amount of office hours, sometimes. When we need to take more time with students we are in a position where we are not getting paid for our craft and profession.”

Professors who work at multiple districts have to keep track of the policies and curriculum at each institution.

“Here at CCC, English 1C requires one full length work and an anthology. Other districts have different standards,” adjunct English professor Guilherme Mylius said. “This creates extra things that you have to do for each class making meeting all the standards more difficult.”

Adjunct anthropology professor Kweku Williams, who commutes from Stockton, asked, “Why is it that people cannot afford to live in the communities that they serve?”

Marshall said, “The transportation aspect is brutal. I almost got run off the road today because someone was road raging.

“I lose a lot of time just driving, and there is always the thought that if something happens to my car… I have no idea what I would do. But for sure I would miss my first class.”

Adjunct anthropology professor Melinda McCrary said that all the adjunct professors work hard to provide quality instruction, but as a part-time professor they are not able to participate in campus culture and keep students updated on campus events.

Full-time faculty are also under pressure due to many departments having only one full-time employee to shoulder all the department’s administrative tasks.

CCC Vice President Academic and Student Affairs Ken Sherwood said that employing adjunct professors is one of the only ways to operate within the college’s limited budget.

“When you hire a full-time salaried employee there is more cost in health insurance and benefits,” he said.

“We have a PR problem right now. Taxpayers look at our outcomes or our success measures and they complain that taxpayer money is being wasted because not enough students are graduating,” Sherwood said.

“For the past five years enrollment has been going down. When funding goes down it becomes more expensive to operate per student and less funding comes in per student.”

Marshall offered another perspective. “You talk about where we could cut costs and then you hear that some administrators are making upward of $250,000 a year. The pay scale for administration is exorbitant.”

Sherwood admits that the pay scale has created tension.

“There really isn’t a significant salary differential between administrators below the presidential level and full-time faculty members. If we did not have as many administrators, the work would just not get done.”

Much of the funding that CCC receives comes with additional reporting duties.

Sherwood does not believe that the frustration of adjuncts is ill-intentioned, but more of a misunderstanding.

Marshall also said that there is a lack of understanding.

He said, “There is no reasonable assurance of further work, even though I have two master’s degrees and 10 years of (teaching)experience. I worry day-to-day with the skyrocketing cost of rent.

“I worry about being homeless. My rent just went up (again),” Marshall said. “I’m very scared.”

Williams said part-time faculty wish the administration would see what they deal with in the classroom; how many combat vets, students with disabilities or emotional trauma they have in class.

Huff suggests that the budget problems originate at the state level.

“When the goal was put in place there was funding that was supposed to be put in place as well. But there have been many more years that the funds have not been made available than years that the funding has been made available,” Huff said. “Decisions about funding are, to a large degree, a consultative process between the governor and state Chancellor’s Office.”

Lightman pointed to the circular nature of the funding problem.

“There’s no way to ‘move the needle’ on student achievement unless we fund instruction and instructional advising like counselors, librarians and student services,” Lightman said.

“The current two-tier system of faculty is particularly detrimental and has been gnawing at our system for well over three decades.”