Vets at odds with administration

Exclusionary decisions leave veterans incensed

Negotiation stalemate: Main points 1) Program leaders phased out 2) Stakeholders group ineffective 3) Veterans’ excluded from decision-making on support services

May 16, 2018

In times of conflict, or when freedom is threatened, Americans intrinsically lean on the strength and stability of those who volunteered to serve in the Armed Forces. However, when integrating back into civilian life, the same level of deference should be shown.

At Contra Costa College, the support system in place to service veterans has been 20 years in the making and now with the two-year-old Veterans Resource Center in place and a handbook outlining available options for integrating into student life, the veterans involved with initiating the program feel they are being systematically phased out.

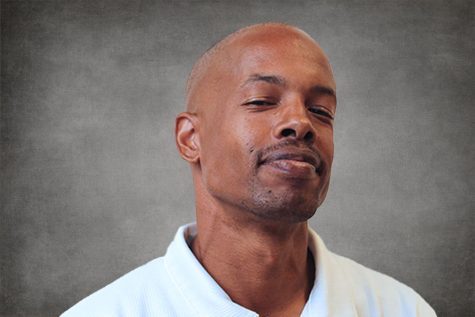

“We started over 20 years ago, going back-and-forth, campaigning to have a place for veterans before finally meeting with former district chancellor Helen Benjamin,” former veteran outreach coordinator Dedan Kimathi Ji Jaga said.

“She was receptive to our proposal. We were promised support, assistance and the awarded freedom to set up a functioning, thriving program to support student veterans.”

He said the program finally got off the ground five years ago under former CCC president Denise Noldon, but the ball was dropped after her resignation.

New life was breathed into the program under the tenure of former college president Mojdeh Mehdizadeh who, along with Ji Jaga and input from other vets on campus, re-established the program.

However, citing his frustration with the campus’ lack of support for the VRC and the college’s veteran population, Ji Jaga resigned as veteran outreach coordinator and office assistant in March.

Campus veterans contend they have been systematically shut out of the decision-making process surrounding services and programs that they were instrumental in establishing.

Consequently, because of their exclusion, veterans club members say campus administrators receive full credit for maintaining the support systems they initiated.

Dean of Students Denis Franco, who also oversees veterans affairs said, “No effort, that I am aware, has been made to restrict veterans or their input in our services. To the contrary, the purpose of having a Stakeholders Group is to obtain input and implement what we can given regulations, district policies, funding and any other considerations that need to be addressed.”

Established in 2016, the Veterans Stakeholders Group consists of college faculty and staff, community members and student veterans.

Despite its intended purpose, the veterans contend none of the veterans on campus with first-hand knowledge of what CCC’s vets need serve in the Veterans Stakeholders Group.

In a May 3 meeting with CCC Interim President Chui Tsang and Vice President Ken Sherwood, five current and former Veterans Club members outlined some of the specific ways that veterans have been slighted on campus.

Current CCC student and former Veterans Club president and campus veteran liaison Leon Watkins said his contract with the campus, paid by the office of Veterans Affairs (VA), was not renewed in 2016. Watkins served as the point-man for veterans support on campus before the VRC was built.

“Because I was the president of the veterans club at the time and the veterans liaison, Admissions and Records Director Catherine Frost said the campus decided not to renew my contract citing a conflict stemming from serving in both positions,” Watkins said.

Under Watkins’ helm, veterans working in the resource center, including Watkins, were given accommodations by the U.S. Army for their work helping students ingratiate themselves back into civilian life as students.

“I didn’t cost the campus a dime,” Watkins said, “I had a contract with the VA and because it came through Admissions and Records, they were my timekeeper. I wasn’t even given a reason why,” he said.

During the meeting, a one-year-old Veterans Club proposal to establish a “victory garden” for campus veterans was used to outline one of the ways veterans were excluded from implementing their own programs.

The project, mired in red tape, has been held up in the Facilities Committee — a committee which somehow omits the vets who initially proposed the idea.

Sherwood, who was aware of the committee, offered no response to the men across the table from him when given the opportunity to explain why they were not a part of the discussions.

Tsang outlined a campus strategy to hire a part-time campus liaison to vets and vows to apply the input of campus veterans toward whittling down the pool of candidates.

Ji Jaga said all of the conversations that take place about ideas that veterans introduce happen without those same veterans’ input.

“If it (hiring a veteran’s liaison) has to go to a committee and you’re not including my voice to answer questions that aren’t being answered, then what good is this process?” Ji Jaga asked.

Before this group of veterans took the lead in molding the veteran experience at CCC, and finding the right information was not a smoothly functioning process.

Current Veterans Club Vice President Zachary Frappier remembers the chore of finding veterans services when he began attending CCC.

“When I came here, nobody spoke to me about being a veteran or helped in setting up my class schedule. I had to seek out that information myself,” he said. “Once I found the center, myself Dedan (Ji Jaga) and some other individuals created bylaws and established a veterans club.”

After establishing the club through Student Life, Frappier said veterans were able to travel to a conference and learned new methods to assist vets in transition.

Now, all the veterans say they need to return CCC’s veterans service programs back to offering vets the backing they deserve is support and access onto the decision-making committees.

“Hopefully, when we have this effort more organized, we can enlist more of the existing knowledge,” Dr. Tsang said. “It’s doable. It just takes time and resolve.”

No definite solutions were brokered by the end of the hour-long meeting.