Chicano image, pride shifts during ‘bloody’ war

Mexican-Americans adjust cultural perceptions during civil, human rights era

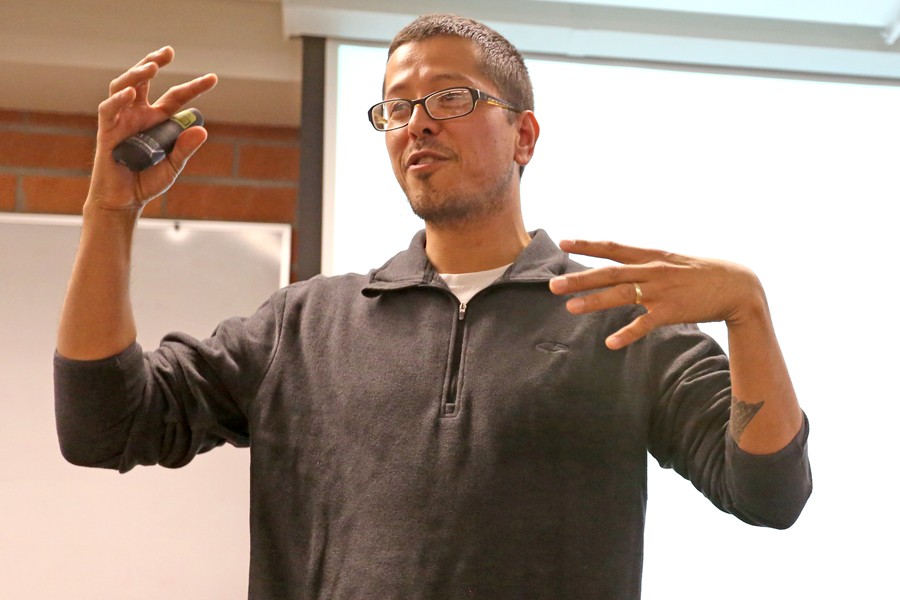

Agustin Palacios, La Raza studies professor, speaks to students during the Big Read’s “Lecture and Discussion of Chicano Participation in the Vietnam War and Their Struggle for Civil and Human Rights in the United States” seminar held in L-107 on Friday.

Apr 21, 2015

Mexican-American involvement in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War influenced young people to redefine the term Chicano and demand social equity during the civil rights movement of the 1960s and early 70s.

La Raza studies professor Agustin Palacios traced the evolution of the term Chicano while giving a condensed, yet comprehensive, history of Mexicans in the U.S. to a group of 25 students Friday in the Library and Learning Resource Center from 12:30 to 1:45 p.m.

His “Lecture and Discussion of Chicano Participation in the Vietnam War and Their Struggle for Civil and Human Rights in the United States” is only one part of the Big Read, which is a month-long communitywide reading program facilitated by West Contra Costa County Library and Contra Costa College, and grant-funded by the National Endowment for the Arts.

West County’s Big Read focuses on Tim O’Brien’s novel about the Vietnam War, “The Things They Carried,” in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the bloody conflict’s end.

“(The Vietnam War) was a very bloody war; lots of people died,” Palacios said.

As many as 80,000 Latinos fought in the “very costly” Vietnam War, and represented 19.4 percent of the 57,605 American deaths, he said.

He said many Mexicans joined the military at the time mainly because of socioeconomic disadvantages, and represented a disproportionate number of deaths during the conflict.

“However, we must also take into account the other side, which had a lot more casualties than the U.S.”

This conflict cost the lives of 444,000 North Vietnamese and 578,00 Vietnamese civilians, he said.

Palacios not only addressed the social unrest that escalated in various barrios throughout the 1960s and early 1970s because of these alarming statistics, but also highlighted misconceptions that Mexican-Americans have about their ancestors’ history, and their evolution of the term Chicano.

He asked the question, what is the difference between a Chicano and a Mexican-American?

He quoted Mexican-American journalist Ruben Salazar for an explanation when he said, “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.

He resents being told Columbus ‘discovered’ America when the Chicano’s ancestors, the Mayans and the Aztecs, founded highly sophisticated civilizations centuries before Spain financed the Italian explorer’s trip to the ‘new’ world.”

Palacios said the term Chicano was not always used as a source of pride.

He said Chicano is an old term that was used by the Mexican community before the 1950s to refer to other Mexican immigrants that look native and poor. It was a derogatory term that was not used as a badge of pride until the 1960s.

“Those poor natives and their descendants took it, turned it into a badge of pride,” Palacios said. “Yes, I’m an Indian, yes I’m poor and yes I’m a Chicano. These youth redefined the term.”

Ebony Mohammed, music production major, was one of the students in L-107 during Palacio’s presentation.

Mohammed said she was given a new perspective on the struggles that Mexican-Americans faced during the Vietnam War after Palacios showed footage from the largest student walkout in national history.

Palacios showed footage of the student blowout during his presentation and it depicted images of police brutality that mirrors the current situation many minority groups are facing today.

“I had no idea that during the civil rights movement we (African-Americans) had the same common enemy as them (Chicanos),” Mohammed said. “The police brutality that brown people faced was just as bad as it was on the black side.”

The video focused on Salazar and the events that led to him being killed during the East Los Angeles protests of 1968 when a police deputy shot a gas canister into a bar that hit him in the side of the head.

“It was during this time period Chicanos began making connections, like why are we fighting in this war?” Palacios said. “And why are we killing (other people who are oppressed)?”

At the same time the Black Panther Party was also making claims that the Vietnam War was not worth its death toll while social injustices continued everyday within U.S. borders.

History major Rose Cowens was also in the audience and said the student walkout grabbed her attention.

“Using this as historical background we should not accept social constructs as they are,” Cowens said. “We now have the Internet, but these people didn’t, and we need to take advantage of this tool.”

Palacios said during the late 1960s, African-Americans and Mexican-Americans realized that they were both victims of a common imperial empire and that is when you saw the rise of the Brown Berets and ethnic studies programs at San Francisco State, which CCC modeled its own after.

“They were less tolerant of the racism in their society and more willing to engage in direct action and protests to change those conditions,” he said.

He said the word Chicano was created after Mexico was colonized twice, first by the Spanish until the Mexican Revolution of 1821 and again during the Mexican-American War from 1846-48 by the U.S.

“This history of colonization, by both the Spanish and then the U.S., has shaped the status, the presence and the sense of self of Mexican-Americans today.”