Football legacy fuels instinctive skills, hunger to uplift others

Athletic genes, intuition gauge Finch’s dedication to school, community

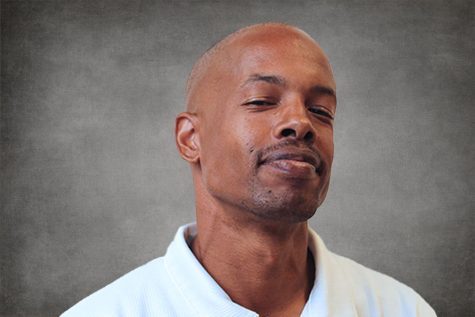

Christian Urrutia / The Advocate

Defensive back Jackson Finch learned the mastery behind tackling and hitting from a young age because of his father. That enabled him to perform well on the field even after experiencing a severe injury during his high school years.

Oct 21, 2015

For an athlete to reach peak performance many variables must come into play; hard work, dedication, sacrifice. But the most important factor comes from within, the intangible for which there is no statistical category.

For Contra Costa College sophomore safety Jackson Finch, football is second nature to him — it is in his blood.

“He (Finch) is a gym-rat. He is a coach’s son. He has great football instincts and pedigree,” CCC football coach Alonzo Carter said. “He is one of those guys that you say just give me a little bit more because he could be special.”

There is a history of football in Finch’s family. His father (first in the family to attend college) played linebacker at the University of Illinois and got an opportunity to play in the NFL as a free agent with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

His older brother, James Finch, played defensive tackle at Tennessee State University.

Born March 24, 1996 in Indianapolis, Indiana as the youngest of four kids, Finch and his family moved to Riverbank, California when James Finch’s (his father) job was relocated.

The move offered the household a welcomed chance at life in a warmer climate.

While his father coached the defensive line at Riverbank High School, Finch (who was barred by his parents from playing football until the sixth grade) began playing quarterback for his youth league.

By 10th grade he was playing varsity for Modesto Christian High School.

“My parents didn’t want me to play football because some of those coaches have kids doing all kinds of things,” Finch said. “My father knew without learning the proper technique for hitting and tackling it can get dangerous.”

The dangers of football became extremely real for Finch before the start of his junior year in high school. Playing quarterback in a practice game he was grabbed by the collar and dragged to the ground, wedging his foot beneath his body.

The tackle separated his ankle and broke a bone in the growth plate in his foot.

On the bright side, when doctors re-set the ankle, the broken bone settled back into place eliminating the need for surgery.

With playing time limited after enduring nine months of rehabilitation, Finch’s father transferred him from Modesto Christian to Central Catholic High across town.

At the time, Central Catholic was poised to make a championship run and all of its skill position players were in place.

Having played defense part time in the past, the now senior was eager to get on the field and prove himself any way that he could. It was then that Finch made the permanent switch from quarterback to safety.

The team finished its 2013 season with a 15-1 record. Finch also nabbed an interception in the team’s 36-23 CIF Division IV Championship win against Bakersfield Christian High School.

Using the season for rehab, Finch was never fully healthy during the championship run — which is why the 6-foot-1, 210-pound safety failed to dazzle college scouts during his senior workout day.

“We did not let him get too down on himself,” James Finch said. “I have gone through injuries so I showed him that he can recover from anything if he stays focused and works hard.”

As a 3.2 gpa student and NCAA eligible following high school, Finch and his father agreed that community college offered a better opportunity to hone his raw defensive talent.

The Comet connection was made when former Carter defensive coach and Finch’s cousin Pat Henderson recruited the safety and introduced the coach to Finch’s dad.

“This (CCC) was the best place for him,” James Finch said. “I respect the way Carter develops his players and teaches them responsibility and how to be strong men.”

After earning four interceptions and 20 tackles in his championship season in high school, Finch leads the Comets with three interceptions after six games this season as a sophomore.

With his father, Finch breaks down most opponents’ game films to learn better ways to interpret their passing plays.

“It is always good to have someone with a wealth of knowledge to talk to,” Finch said. “Learning to understand tendencies and how to be in the best position possible to make a play is key.”

CCC receiver Malcolm Hale played against Finch in high school and recognizes the strides he’s made in his game.

“He is maturing. He plays smarter now. In high school it was more about natural ability and less about technique,” Hale said. “Finch is a good player and captain. He is not out there playing for himself — he wants everybody to shine.”

The product of a solid nuclear family, Finch regularly saw his father help people from all walks of life and serve as a positive role model for those who did not have anyone to look up to in life.

“My father was always helping someone. I want to be someone people depend on like him,” Finch said.

“I want to give back to troubled youth. That’s why I chose sociology as a major,” he said. “I didn’t have to experience the worst in life to know the world can use more positive people to uplift others who need help.”