Former Black Panther dissects political fallout

Author discusses party’s lingering message 50 years after inception

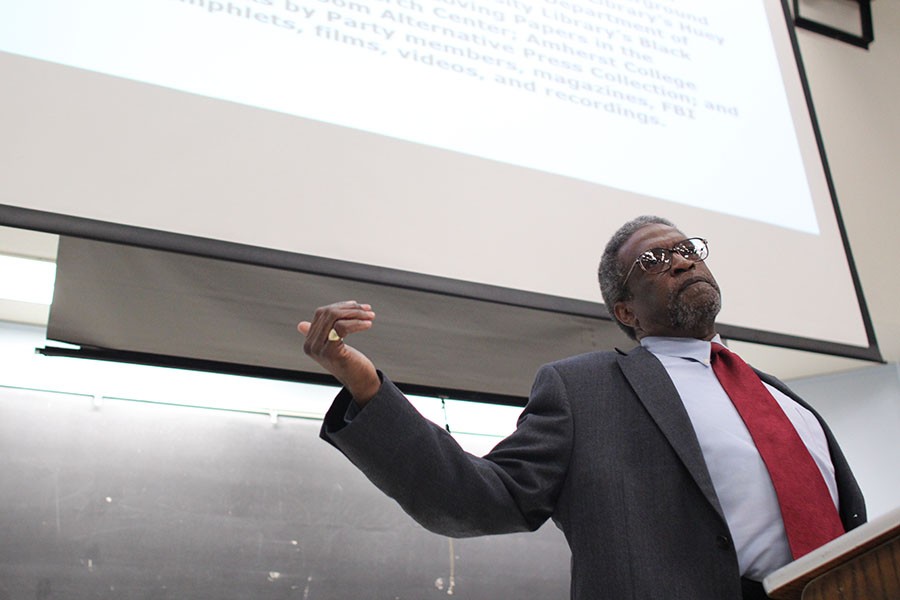

Christian Urrutia/ The Advocate

Dr. Paul Alkebulan speaks with students about his involvement with the Black Panther Part in Oakland from 1969-72 as a student activist during the “Reflections on the Black Panther Party” seminar on Saturday in LA-100

Mar 2, 2016

To honor its 50th anniversary a former Black Panther Party member discussed the organization’s decline, local origins and the political marginalization of the family structure.

As part of a W.E.B. Du Bois Lecture Series at Contra Costa College, author Dr. Paul Alkebulan, 68, opened “Reflections on the Black Panther Party: A Retrospective Seminar on the 50th Anniversary of a Social Movement,” by talking about his experience as a Black Panther and finished the event by answering questions.

Social sciences department Chairperson J. Vern Cromartie invited 100 students to listen to Dr. Alkebulan, ask questions and watch “Merritt College: Home of the Black Panthers,” on Saturday from 1 to 4 p.m. in LA-100.

Hashim Alezzania, a political science major, said he learned that the Black Panther Party worked with the Brown Berets, the Nation of Islam, the Red Guard and were not as radical as mainstream media outlets reported, but organized many community outreach programs that educated people about racial injustice in education and the electorate.

“Let’s not regret the past and be grateful that we are able to express ourselves politically,” Alezzania said. “These people not only helped their own group but everyone in our society. But still, it is a shame not everyone was taught that America is a nation based on diversity and not white values.”

Alkebulan discussed his involvement with the party during his early 20s as a student activist in Oakland from 1969-72 and the internal power struggle, arrests and the FBI’s cointelpro program that contributed shutting down all its international and domestic chapters by 1982.

His main concern was the family structure in African-American communities being devastated by the outsourcing low-skilled manufacturing jobs in the 1980s.

“It shut off avenues of employment for unskilled men and women in many communities. It created a change in a culture in which marriage was once the focus of our efforts,” he said. “Now it is not the big prize and the stigma of wedlock doesn’t happen as much anymore.”

Jose Avila, a business major, said. “Without a family you don’t have that mental support to keep moving forward to be successful in anything you choose.”

He said like the Panthers, the Black Lives Matter Movement has the momentum of its generation.

“Activists now need to take advantage of what the civil rights movement accomplished,” he said. “Now black people and people of color have the right to vote, to travel freely and pursue an education.

“We are represented in all branches of government, judicial, executive and legislative. Even the police is (racially) integrated. We need to use this as leverage to restore the family structure in America, not on a civil rights level, but in the community.”

Alkebulan said the party started in 1966 when leaders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton followed police officers with guns and law books to read victims their rights and hold non-violent armed sit-ins.

In 1967, he said its members stood at the Capitol steps with guns to oppose a bill that would restrict citizens from the right to carry loaded weapons in public.

He said that the Black Panthers were often thought of as militant socialists after, but they wanted the ability to protect communities from brutal police practices.

Despite the negative media coverage, Alkebulan said the Panthers survived for 16 years by providing community training through constitutional rights and welfare programs, using their underground newspaper to spread a creed inspired by the ideologies of human rights leader Malcolm X.

“I wanted to make a difference,” Alkebulan said.

He said he regrets many members were attracted to an ideology of an armed struggle instead of programs like its Free Breakfast for Children Program — an activity he and his family participated in every morning.