Alumnus shares Olympic experience, hopes to inspire

[email protected] / The Advocate

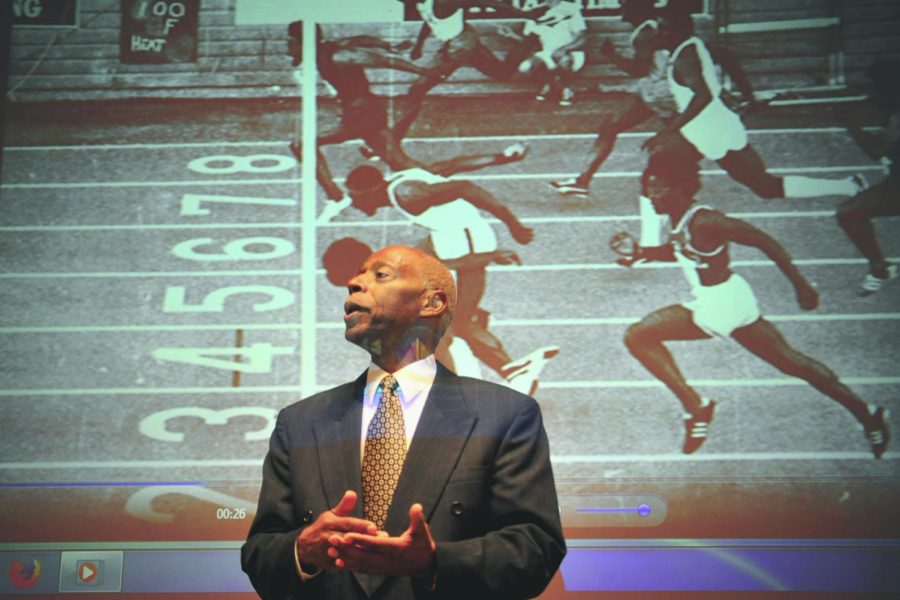

Munich Summer Olympic Games gold medalist Eddie Hart stands in front of an image of the moment he won his Olympic qualifying race during a speech to students about his book, “Disqualified: Eddie Hart, Munich 1972, and the Voices of the Most Tragic Olympics” in GE-225 on Feb. 21.

Feb 28, 2018

Find your dreams and never give up on pursuing them was just a dose of the words of wisdom gold medal Olympian and Contra Costa College alumnus Eddie Hart gave the audience during his book signing event for his new novel “Disqualified: Eddie Hart, Munich 1972, and the Voices of the Most Tragic Olympics,” presented Feb. 21 in GE-225.

“No one has to believe in you but you,” Hart assuredly told the crowd. “You have to save your own life.”

His new book gives an account of the monumental events that transpired at the 1972 Summer Olympic Games in Munich, Germany. At the forefront of his presentation was the unfortunate scheduling mishap, which led him to miss competing in that year’s men’s 100-meter competition.

Hart was introduced by co-author and award-winning retired Bay Area sportswriter and columnist Dave Newhouse, who covered the 1972 Munich games for the Oakland Tribune.

Before introducing the Olympian, the legendary journalist described a few of the unprecedented events that occurred at the Munich games.

He recalled an incident involving pole vault champion Bob Seagren taking home silver after being forced to compete with unfamiliar poles and America’s controversial loss to the Soviet Union in basketball.

The defeat handed the U.S. its first loss in the sport since it was inaugurated on the Olympic level in 1936.

The games also have the distinction of being the only sporting event to be targeted for a terrorist attack. Newhouse detailed the murder of 11 Israeli athletes and coaches and a German police officer by eight Palestinian terrorists during a hostage crisis in the game’s Olympic Village.

Journalism major Robert Clinton introduced Newhouse following a brief description of the event by Student Life Coordinator Joel Nickelson-Shanks.

Clinton said although Newhouse’s reign was before his time, the journalists that influenced Clinton were inspired by Newhouse and his work, also making him a student of his craft.

As a testament to passion and perseverance, Hart described his personal journey to becoming a gold medal Olympian, which, for him, started at the age of 13.

Hart said he coupled his love for running with his inspiration of becoming “The World’s Fastest Human” and began running track in hopes of one day representing the U.S. in the Olympics.

After graduating from high school in Pittsburg, Hart began his college track career at CCC in 1967.

It was here that he began to hone his sprinting skills to a professional level.

Hart said he gives an ample amount of credit for his success to CCC — the campus where he officially began his career.

“There’s no place like home,” he said with an exuberant smile. “Every time I set foot on this campus I get emotional. This is where it all started.”

From CCC, Hart went on to attend UC Berkeley where he continued to excel in track. He placed first in the NCAA Track and Field Championships in the 100-meter sprint as a Berkeley student in 1970.

Hart said his passion for track eventually led him to the 1972 U.S. Olympic Trials where he ran the 100-meter sprint in 9.9 seconds. The feat duplicated that era’s world record and earned Hart’s position on the U.S. Olympic team.

With his invitation to represent America in the men’s 100 and the men’s 4×400 meter relay in Munich, Hart was in arms’ reach of obtaining his childhood dream.

But he was seconds too late.

Hart and his teammate Rey Robinson were both eliminated in the 100-meter race because their sprint coach, Stan Wright, unknowingly used an outdated Olympic schedule to determine the start time of the quarterfinal heat.

Hart said when they realized what had happened the team sprinted to the official track, but it was already too late.

He missed the opportunity to compete in the race of his dreams because of a scheduling discrepancy.

“If I didn’t know what pain was before that day, I did then,” Hart said. “Putting 10 years of work to get that point and miss my chance, it felt like losing a child.”

However, Hart did anchor the 4×400 meter relay team, which won the final heat and matched the existing U.S. held world record of 38.19 seconds.

Along with his team, Hart became a gold medal Olympian.

Though he was disheartened by missing his moment to compete in the 100, Hart said he didn’t use it as an excuse to give up. He said his misfortune at the Olympics taught him the important lesson of learning the difference between reacting and responding.

Hart said when things happen to you, you can either react — let the issue dictate your actions, or you can respond and step up to the challenge while striving to become the person you want to be.

Sociology major and Comet safety Damion Tingle said Hart’s speech left him inspired to chase his passions.

John Lamb • Oct 1, 2020 at 3:28 pm

Hart’s 1972 Olympic gold for the relay was for the 4×100, not the 4×400. There was an entirely different disqualification story for the 4×400 that year.