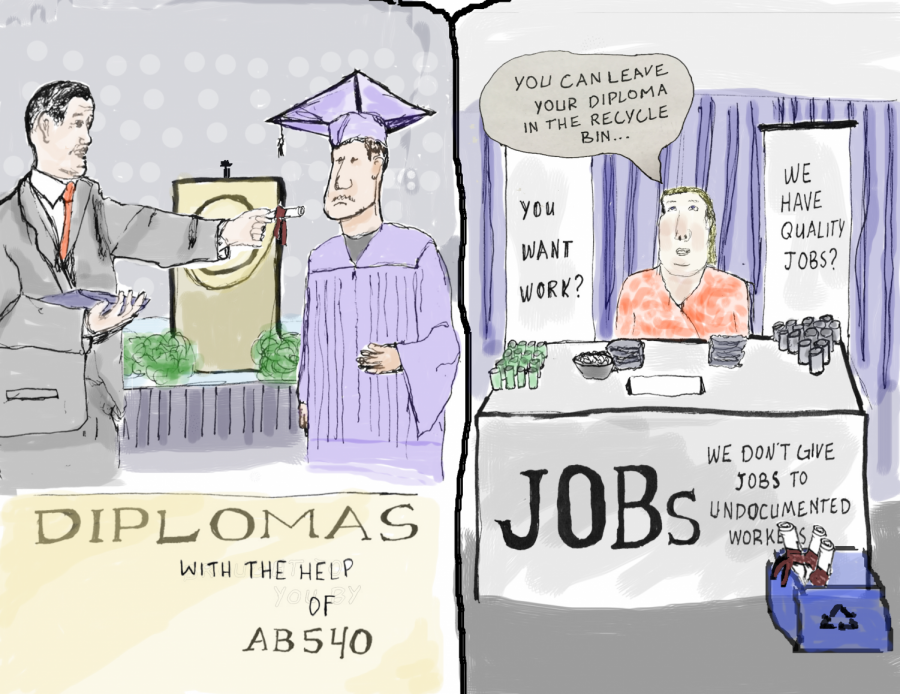

AB 540 students face dead-end opportunities

Apr 17, 2018

Last October, Gov. Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 68 in an attempt to offer the prospect of a cost-effective education to a wider swath of California’s undocumented student population.

But after these students graduate into the workforce, is there a similar safety net to help them find gainful employment en lieu of their undocumented status.

According to the bill’s author, Sen. Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens), SB 68 enables students to count years spent at a California community college or adult education toward AB 540 eligibility.

Furthermore, the bill will allow the completion of an associate degree or satisfaction of the minimum requirements to transfer to the University of California (UC) or California State University (CSU). But after graduation, how do these students earn a living wage?

Legislation has been introduced in the past to ease the educational strain on California’s undocumented community, but without work permits or a clear pathway to citizenship, the problems always remain the same.

SB 68, which serves as an expansion to the landmark 2001 legislation AB 540, makes it possible for undocumented students at community college and other programs eligible for in-state tuition and financial aid.

Prior to SB 68, undocumented students would have to have graduated from and spent a minimum of three years in a California high school to qualify for in-state tuition. However, most undocumented students who grew up in California were forced to pay international student fees because they could not establish legal residency or had finished their secondary education in their native countries.

In order to ensure the state is not expanding a pool of people in an extremely qualified, yet legally unhirable demographic, the same energy Californians generate in support of AB 540 recipients should be afforded to that same immigrant population after graduation.

California should lead the way in offering work permits for AB 540 recipients, AB 68 graduates and DACA students to counteract President Donald Trump’s offensive on sanctuary cities.

Sure, students who were once barred from receiving a quality education because of financial restrictions can now attend college, but then what?

A lawyer who can’t practice law, a doctor who can’t practice medicine and thousands of undocumented graduates accepting jobs that they may not have gone to school for isn’t the right that so many of California’s students are fighting for.

Programs like the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals that granted work permits, offer a significant percentage of undocumented youth a chance to work legally.

In California since January of 2015, residents who cannot establish a legal presence in the United States may still apply for a driver’s license — the same should apply for a work permit.

But today, new anti-immigrant laws are fueled by the demonization of the undocumented community as criminals. The mentality of this White House and many in its administration is one that values discriminatory laws rather than protecting the most vulnerable human interests. It is far-fetched in the eyes of the law, but only a small step in the eyes of a deserving community which has braved the path to earn their right to work high quality jobs.

Carmella • May 13, 2018 at 4:59 pm

Our country continues to help illegals at the expense of Americans. They are getting help with college and other things while Americans get to support them. We are starting to feel like America is discriminating against Americans