Hardships spark change toward education

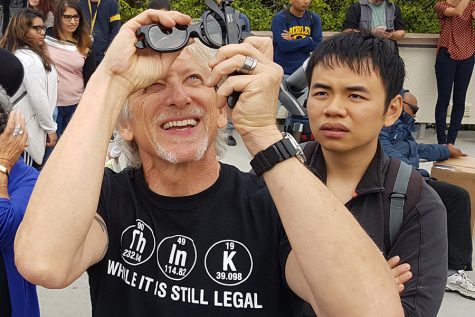

Grabbing a coffee in San Pablo, Fairchild makes herself available on the phone for last minute schedule changes on Tuesday morning.

October 30, 2017

Victoria Fairchild has never missed a phone call. She is there for her friends in the early morning hours or late at night, on weekends and weekdays. She even picks up on her birthday to talk.

When talking on the phone with a colleague about a client, she speaks with the confidence and understanding of someone who knows each step and pitfall along the path toward recovery from addiction.

“Four years, five months and 11 days ago I was pushing a shopping cart in a homeless camp and I thought I was going to die a hopeless dope fiend,” Fairchild said.

She has an app on her phone that counts the days she has been sober.

Fairchild is a case manager at the Portia Bell Hume Behavioral Health Center.

“I work with clients that have severe mental illness like schizophrenia and clients that society and everyone else has given up on,” Fairchild said.

She got the job through taking the health and human services (HHS) Service Provider Individualized Recovery Intensive Training (SPIRIT) courses at Contra Costa College.

SPIRIT is a three-course program that offers a certificate in peer support.

The program is designed to help students who have faced drug addiction and other forms of mental illness transform their recovery process into an educational experience that develops valuable professional skills for the mental health field.

HHS professor and department Chairperson Aminta Mickles developed the SPIRIT program.

She said she has seen many students, including Fairchild, find success through the program, but she knows it is especially hard in the beginning. One thing that is noticeable about Fairchild is that she treats every moment as a success.

Fairchild said, “I’m living a dream right now because I thought I would die a hopeless dope fiend. Today I am doing things that I never could have imagined. I have my own place. I bought a car. Doing normal things are miracles for me.”

Fairchild said it is important for people to keep their confidence up if they are in recovery from addiction.

Keeping track of their successes, even if they are small, and constantly reminding themselves how well they are doing, is essential, Fairchild said, as she unfolded a printout of her grades that was in her pocket.

The number at the bottom that is triumphantly circled in pencil reads: “3.842 GPA.”

At CCC, Fairchild has found those opportunities to build confidence.

She has been the Inter-Club Council representative for the Health and Human Services Club and for the Corrections to College Club.

She has spoken about her recovery for educational conferences and she won four scholarships, including $1,000 for school expenses that she used to purchase gas cards for her commute. She credits her support structure for helping her believe that she could succeed.

“My professors all worked with me because I used to think I was dumb. I struggled in

school and was a straight F student. I struggled to read. It took me seven times to pass the GED. I had dropped out of ninth grade,” Fairchild said.

She said she wants to get her associate degree and eventually go on to study psychology in a program that UC Berkeley has for formerly incarcerated students.

But for now, she said, she is setting achievable goals while focusing on her job and studies at CCC.

“I have to live in the now. Once I accomplish one thing I can go to the next and on to the next thing after that, but if I think about all the things that I will have to do over the long term, it stresses me out and I get scared,” Fairchild said.

The success that Fairchild found at CCC did not come easy.

She had a long path just to get to the point where she could return to school.

“I was in and out of prison from when I was 21 ’til I was 38. I have been to Valley State Prison for Women (VSPW), I have been to West County, I have been to San Joaquin County. Now I am paying off debts and I have most of my records expunged.”

Fairchild said she got her GED while in prison. “I was making 8 cents a day and I said to myself, ‘There has got to be something different.’ I said to my (prison case worker) ‘I feel like I have rabbit in me. I want to get my GED’.”

Fairchild said while she was inside San Joaquin County, a man she calls Mr. McCullough helped her learn to write essays.

“I was terrified of essays. I felt for sure that I would never be able to write one.

“He wrote down a list of questions and said, ‘Just answer these questions about your topic. Use these ones in the beginning, these ones in the middle and these ones in the end’.”

When it came to writing essays for her GED, McCullough said to Fairchild, “Remember those questions. Just answer those same questions and you will be fine.”

She did, and she passed her GED.

Fairchild said she got close to finding her track a number of times, but failed because some of the necessary ingredients for success were not there or she had not yet reached a point of healing.

“I went to a program for 90 days and as soon as I got out I went and used again. I want- ed to do the right thing, but I did not have the support group,” Fairchild said.

“The last time I ever went to jail I was able to express some things from my past to one of the counselors. I just needed someone to just listen. I told the counselor about being molest- ed as a child.

“Somehow, finally talking about it stopped me from self-destructing and going to jail. I quit stealing, I quit taking from people, but I still couldn’t stop getting loaded.”

The real turning point for Fairchild came when she went to a funeral for her uncle.

His sister got up and said, ‘You know that Jackie. All he wanted to do was smoke drugs all his life and that’s what he died doing.’”

Fairchild said she has two kids and did not want them to say that about her.

“I stopped using and went to stay with my aunt in Orlando (Florida). Forty-six days later I was clean and still miserable.”

Fairchild said she grabbed a pamphlet about Narcotics Anonymous (NA) from a stand at a local fair.

“My aunt had gone on vacation and left me at the house alone. I knew I had a round trip ticket to return to the misery that I had in Richmond,” Fairchild said.

She went to an NA meeting and found herself surrounded by people who had gone through similar things as she had.

“Everyone at that meeting hugged me and told me that they would love me until I learned to love myself,” Fairchild said.

With the support of her new NA family, Fairchild said she was able to learn to adapt to sobriety. In her first year she became a wildlife fire fighter in Northern California.

“The job was very physically demanding and sometimes we had to hike uphill all day long. This is where I learned to just keep moving even if you can only go two inches at a time. Once you stop, you lose your momen- tum,” Fairchild said.

When the fire season ended she began to take automotive classes at Butte College, but she said things were just not clicking.

Fairchild said she heard about the health and human services program at CCC but was afraid to go because that was the area where she had gotten into so much trouble.

“But I took the risk and did it. I have been really happy with that decision,” Fairchild said. She said the program has not been easy and she still has a good deal of her general education requirements to take before transferring. “Fear is a big part of what you are dealing

with in the recovery process,” Fairchild said.

“I have lived a life of ‘I can’t’ and now I can’t

say that. I have proven to myself that I can.” CCC Learning Disabilities Specialist Alissa Scanlin said when students who have faced challenges in life go back to school they often

have to catch up and that can be frustrating. “When students in recovery come to college it’s like starting life all over again,” Mickles said. “They don’t know if they fit in or if they are too old. They don’t know if they can meet the requirements of a full-time student.”

Mickles said when students are guided by peers and teachers, there is a much higher success rate. “I believe that everybody has the ability to succeed if they are nurtured.” Fairchild said, “My kids are proud of me for the first time. I was able to contribute to my daughter’s graduation party. That meant alot to me.

“My family is proud of me, but I don’t have — I lost all their childhood because of my choices,” Fairchild said with tears filling her eyes.

She said experiencing pain helps people grow. “Anybody who is going through the things I have gone through (should know) there is light at the end of the tunnel and if anybody needs someone to talk to, I can help.

“Don’t give up on yourself. Recovery is a miracle.”